Rethinking Primary Prevention

A collaboration between Professor Michael Salter (UNSW) and Jess Hill

This paper is based on two presentations, delivered at The Hatchery conference on Ending Coercive Control (July 2023) and the Stop DV Conference in Hobart, Tasmania (December 2023). It is the result of countless conversations with advocates, academics and victim-survivors over many years. Thanks to the many people who have helped shape these ideas, and who have since shared them with decision makers across state and federal governments.

To clarify right upfront, this paper is specifically critiquing the intersection between prevention agencies and governments (federal and state), and how prevention work is conceptualised, resourced and funded. We are not critiquing organisations doing frontline education work on consent and respectful relationships. Such education and engagement is vital, and governments should provide adequate funding for organisations leading this work.

Every time there is a cluster of domestic homicides, or a high-profile femicide that horrifies the public, there is a wave of anguish and soul-searching across Australia about how to prevent violence against women.

We are primed to wait for the next murder; one that will shake the public and create sufficient media noise for politicians to respond. The murder of Luke Batty by his father on a cricket pitch in Victoria in 2014 was one such homicide. It was public, it was witnessed, and it was followed by the phenomenal advocacy of Luke’s grieving mother, Rosie. That led to a nationwide awakening on family violence, as well as the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence, and world-leading investment from the Victorian government.

In 2020, the murder of Hannah Clarke and her three children by Rowan Baxter – again public and horrific –brought the issue of coercive control to national attention. This has been a landmark development. The coercive control lens reveals that most domestic abuse is not just a series of consequential incidents, but an unrelenting system of entrapment of the victim by the perpetrator who uses everything at their disposal to enforce their will over the victim and their children. It often continues long after the relationship is over and is a consistent dynamic preceding almost all domestic homicides (NSW Domestic Violence Death Review Team, 2020). Hannah’s grieving parents, Sue and Lloyd Clarke, as well as Nithya Reddy (sister of the late Preethi Reddy) here in NSW, also played a crucial role in getting coercive control recognised and legislated against as a crime. Federal politicians with their own publicly disclosed experiences of coercive control, namely Linda Burney MP, Anne Aly MP and Senator Jacqui Lambie have also contributed to campaigning for a nationally consistent response to criminalising coercive control.

When another domestic homicide forces the issue back onto the front page, journalists ask experts, ‘What can we do to fix this?’ While some responses often give a nod to practical interventions, like adequate funding for services and increased public housing, the primary answer from major prevention agencies, almost always centres on one solution: combating gender inequality and harmful social norms. No matter the nature of the incident, the dominant commentary is always the same: we all have a role to play in ending gendered violence, and we can do that primarily by challenging harmful norms and calling out our mates when we hear them ‘disrespecting women’.

This is the ‘gender equality’ approach to preventing gendered violence (in academic circles, it’s known as the ‘ameliorative hypothesis’). As the theory goes, gender inequality is at the root of domestic violence; ipso facto, as gender equality improves, victimisation rates will fall. For more than a decade, Australian governments have invested significant time and money on programs and awareness campaigns to change harmful social norms and attitudes in the hope that doing so would ‘stop violence before it starts’.

The ameliorative hypothesis has a long history. It was advanced by first-wave feminists in Australia in the 19th century, when the suffrage campaign for the vote was often characterised in cartoons and newspaper columns as a way for women to protect themselves against cruel and violent men. As Janet Ramsay writes, “the message of the cartoons is that women needed the vote to defend themselves (through directly policy influence), and that they were helpless without it.”

Since women won the right to vote, they have made greater progress towards gender equality than at any other time in Western history. Subsequently, we have seen reductions in the prevalence and severity of physical violence and domestic homicide. But sexual violence continues to be perpetrated at high rates, and what we now refer to as coercive control continues to increase in complexity and severity. Indeed, the forensic social worker who popularised the term, Evan Stark, argues that, while women’s equality ‘made violence less effective as a means through which men could control (women)’, a ‘significant subgroup of men chose to protect their privileges by devising coercive control, a strategy that complimented violence with other tactics…Greater equality has reduced severe partner violence against women, allowed them to resist abuse more effectively, and made it easier for women to separate from abusive men” (Stark 2007, p 76). But the overall likelihood that a woman will be abused by a man has not changed. “This is because”, Stark writes, “men have expanded their oppressive repertoire in personal life, and governments have tolerated them doing so.” This paradox appears to be most evident in the Nordic countries, with the world’s highest levels of gender equality, as we will explain in detail later in this paper.

The ’ameliorative hypothesis’ gained traction again as a public policy response in the 1990s. ‘Violence is an extremely complex phenomenon with deep roots in power imbalances between men and women, gender-role expectations, self-esteem and social institutions,’ wrote the American academic Lori Heise, in her influential 1994 paper. ‘As such, it cannot be addressed without confronting the underlying cultural beliefs and social structures that perpetuate violence against women. In many societies women are defined as inferior and the right to dominate them is considered the essence of maleness itself. Confronting violence thus requires re-defining what it means to be male and what it means to be female’ (Heise, 1994, p 142). (It's worth noting here that increasingly, this binary view of gender is becoming less meaningful, particularly for young people.)

This population-wide approach to changing hearts and minds is at the centre of Australia’s plan to prevent violence against women and children.

But to date, this strategy has not shown the kind of results we should be seeing, especially after such significant levels of investment. Prevention agencies defend this as ‘generational change’ (ie. it won’t produce short-term results) but simultaneously support the Australian government’s firm commitment, under the National Plan, to end violence against women and children in a single generation.

According to multiple metrics, the gender equality approach has not only failed to actually reduce and/or prevent violence, it has achieved only marginal improvements to community attitudes over the past decade. We may be world leaders in funding and developing primary prevention – and that is certainly laudable - but we are not world leaders in actually preventing violence.

In case there is any confusion, we want to make it clear that we do not dispute the link between gender inequality and gendered violence. Gender inequality is both a cause and a consequence of gendered violence. However, we know from international evidence (and history) that greater rates of gender equality are necessary but not sufficient for the prevention of gendered violence. We are not suggesting that the gendered violence sector abandon the project of gender equality as an important goal, but we do dispute a disproportionate focus on ‘gendered drivers’ of violence, both in analysis of the problem and the parameters of the prevention response.

We’re proposing that governments and funded agencies reorient their focus onto the most effective evidence-based strategies to prevent violence and its impacts in the short-to-medium term. We need, as Stark notes, for governments and systems to cease tolerating the use of oppressive techniques in personal life. Ultimately, the sooner we reduce gendered violence and its impacts on victim survivors, the sooner we will see increased gender equality for all. The approach must be multi-faceted. The longer-term approach of ending gender inequality should remain in our frame of reference, but not at the expense of other timely and more urgent interventions to keep women and children safe.

Our analysis of this problem is not new, and it is not ours alone. For many years, Indigenous scholars and advocates in particular have critiqued this liberal feminist approach to prevention and have repeatedly emphasised the need to focus on intergenerational trauma and wholescale systems change, among other priorities.

Increasingly, many frontline workers, experts and victim survivors (groups that are not mutually exclusive of each other), faced with an increase in the complexity and severity of coercive control and sexual violence, have also become concerned with the doctrinal rigidity of Australia’s prevention strategy. But the ameliorative hypothesis has become a sacred cow. Many critics consider it too risky to question or criticise it publicly, so for the most part, they have been voicing these concerns privately, with growing urgency.

We cannot keep having these conversations in private. Like other sectors faced with entrenched public health problems, we need to have the courage to have difficult conversations with each other – and with government - about what is and isn’t working. More importantly, we need to have the courage to change direction.

For at least the past 20 years, the global response to gendered violence (Australia included) has been devised as a public health response. The landmark publication of the World Report on Violence and Health in 2002 by the World Health Organisation articulated the emergent international consensus that interpersonal violence, and particularly gender-based violence, was a public health priority and should be addressed as such. It’s from the public health model that we get the three response tiers: primary, secondary and tertiary responses.

We are a nation famed worldwide for our effective responses to other public health issues – from thwarting the tobacco industry to reducing road deaths and preventing HIV. These monumental achievements did not come easy; they required courage and innovation. A decade ago, framing violence against women as primarily a problem of gender inequality was also innovative. Much good work has been done in this area, and should continue, but it’s our opinion that our central prevention strategy has become too ideological, exclusive, and sometimes contrary to evidence. If we are to even reduce the rates of violence against women and children in a single generation – let alone end gendered violence altogether - we need to fundamentally rethink our approach to primary prevention.

****

For many public health problems, tracking prevalence rates is simple: the number of infections or other negative outcomes goes up or down. For gendered violence, there are few neat indices for success or failure (with the exception, arguably, of domestic homicide rates). Rising numbers of police callouts don’t necessarily indicate an increase in violence. An increase in these statistics may, in fact, indicate success, in that victim survivors feel more confident to report. In fact, the sustained increase in reporting rates shows that we are seeing a generational shift in women’s willingness to report domestic, family, and sexual violence to police. Because tracking prevalence is not clear-cut, we need to think through questions of primary prevention especially carefully. What is primary prevention? What does success look like? How can we hold ourselves accountable to victim-survivors, and to the public?

Let’s get clear first on what ‘primary prevention’ actually means.

As the Encyclopedia of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion defines it, primary prevention involves activities that:

a) prevent negative or harmful outcomes

b) protect healthy, safety and wellbeing, and

c) promote improved outcomes for a population of people in three possible contexts:

- universally (as a basic utility for everyone’s benefit);

- selectively (for groups at risk); and

- for groups considered to be at very high risk (Bloom & Gulotta, 2014, p. 3).

Depending on the context and the problem, primary prevention may focus on the “total population”, as was the case with Covid-19, or it may be targeted at specific communities. In Australia, in the face of an HIV epidemic that has particularly impacted gay men, for example, there was no point in targeting the whole community with intensive interventions. Instead, public health efforts focused on the communities most affected, and spent money where interventions were going to be the most effective. The aim is to reduce prevalence and incidence: that’s the ultimate goal of prevention.

In Australia, the current primary prevention strategy on gendered violence takes a universal approach. It does not put more resources into certain groups, but rather tries to deliver prevention work across the entire population. So entrenched is this ‘universal’ approach, it has come to stand as the exclusive definition of primary prevention.

But we are now coming up against the limitations of this approach. Even if we accept the current theory of change – that improvements to community attitudes will reduce gendered violence - it is clear, from the survey data we rely on to measure attitude change, that the strategy we have pursued for the past decade is showing limited, if any, success.

The success of Australia’s primary prevention work is measured in the National Community Attitudes Survey, which comes out every few years; the 2021 NCAS surveyed 19,100 Australians on their attitudes towards and understanding of violence and gender equality. On some metrics, we have seen big improvements; for example, in 2013, 54% of respondents stated that controlling a partner by denying them money was always or usually a form of domestic violence. This rose to 66% in 2017 and 81% in 2021.

However, when it comes to attitudinal rejection of violence towards women, the results are poor. The most recent NCAS in 2021 revealed “there was no significant improvement between 2017 and 2021 in attitudes towards violence against women overall’ (Coumarelos et al, p. 83). If you look more closely at the Sexual Violence Scale of the NCAS, which measures attitudes towards sexual violence, the mean score has improved marginally, from a score of 66 to 68. Given the time period this covers, we would expect to see much greater improvement: the years between 2017 and 2021 were a period of extremely high awareness and traction on issues of gendered violence. From late 2017, the #MeToo movement dominated headlines, and in 2021, gendered violence became a national focus after allegations in federal parliament and nationwide women’s justice marches.

As the NCAS shows, despite intense media coverage and extensive public conversation, alongside large investments in changing social attitudes, the results are underwhelming. In 2009, before investment and awareness campaigns in this area began, the mean score on the AVAWS (attitudinal rejection of violence against women scale) was 63. This scale measures ‘how strongly respondents reject problematic attitudes regarding violence against women’ (ANROWS). The higher the score, the stronger the rejection of ‘incorrect myths or problematic beliefs concerning violence against women’. Eleven years later, in 2021, that percentage had only risen to 68 - a mere five points.

The data improves somewhat when you look at the attitudes of young people (aged 16-24) towards sexual violence, which improved by three points (from 66 to 69) between 2017 and 2021. Like adult Australians, however, their attitudes towards domestic violence had stalled during that period (Coumarelos et al., 2023, p.47).

However, in the very area where we have seen some improvement in young people’s attitudes, we have also seen an alarming rise in perpetration.

Between April and October 2021, 8,500 respondents were surveyed for the Australian Child Maltreatment Study, including 3,500 people aged 16-24. These results told a very different story to the NCAS. While child sexual abuse by adult perpetrators had decreased significantly over previous decades, abuse by known adolescents in non-romantic relationships has in the past few years increased, to become the most common perpetrator category for victimised young people now aged 16-24. This is a significant and recent change. Historically, adults were the most common perpetrators of child sexual abuse (and still are, for people aged over 25). Now, the most common sexual offender against children is another child. These statistics are alarming on their own, but they should also raise alarm bells about the potential for future perpetration, because sexual violence in childhood is a risk fact for other violence, including domestic and family violence in adult relationships (ALSWH, 2022).

This seeming mismatch between attitudes and behaviour raises serious questions.

If the rates of child perpetration continue to rise, we may conclude that attitudes do not reliably correlate with behaviour. Psychologists refer to this as ‘attitude-behaviour inconsistency’. A stated attitude doesn’t necessarily match or predict that person’s behaviour. As Joan Didion once wrote, ‘it is possible for people to be the unconscious instruments of values they would strenuously reject on a conscious level’. We see this reflected in perpetrators who condemn violence in one breath and assault their partners in the next. This disconnect is well known to professionals who work with perpetrators. It is just one of many gaps between their stated attitudes and their actual behaviour.

Alternatively, it may be that the promising increase among people aged 16-24 who reject violence-endorsing attitudes comprise a different cohort from the one most likely to perpetrate gendered violence. If so, we can conclude that efforts to change attitudes are not reaching those young people most at risk of perpetration.

Either way, we can see that, at least in the short-to-medium term, overall improvements in attitude change amongst young people have not correlated with a decrease in gendered violence perpetration.

This gap between attitudes and prevalence requires urgent analysis. The NCAS results are currently the primary measurement tool for assessing the success of the National Plan to Eliminate Violence Against Women and Their Children. But what is it really telling us?

Reducing gendered violence is urgent work. Since the federal government has committed to ending gendered violence in a single generation, we believe that we not only have an opportunity, but an obligation, to pivot. It’s our position that federal and state governments need to urgently consider whether they should continue to invest so much time, money and effort into a strategy that is achieving limited results in terms of community attitude change and is not leading to a reduction in gendered violence.

****

Australia has a proud history of public health prevention success stories, many of which have hinged on the capacity to experiment and change course once an embedded prevention strategy has started to deliver diminishing returns. This is particularly salient in the campaign to eliminate HIV/AIDS.

When HIV broke out across high income countries in the 1980s, Sydney was one of its global epicenters. Across Australia, we lost thousands of men, women and some children to HIV.

Today, Sydney is one of the first cities in the world to be on the brink of eliminating HIV. Since 2010, new HIV infections have fallen by 88 per cent in inner city Sydney postcodes with large communities of gay men (Thomson, 2023). In 2022, only 11 new cases were recorded in central Sydney.

The Australian prevention response to HIV has always been world leading, and that is largely due to it to being led and driven by those most affected: the LGBT community sector, as well as organisations for sex workers and people who inject drugs.

But the key to HIV prevention is that it has been selective, not universal. It focuses on communities most at risk.

Curiously, heterosexual people often speak favourably of the Grim Reaper ad campaign of the 1980s. Television and newspaper advertisements depicted Grim Reapers bowling down tenpins of everyday Australians, from babies to footballers and housewives. The three-week campaign left an indelible impact on the Australian consciousness. "At first, only gays and IV drug users were being killed by AIDS," the ads said, "but now we know every one of us could be devastated by it".

HIV prevention experts tell a different story. Despite the mythology that has accumulated around the campaign decades later, evaluations after the campaign found it was confusing and ineffective (Stylianou, 2010). It advertised to people who weren't at risk and positioned those most at risk - largely gay men - as the Grim Reaper coming to destroy suburban families.

Repeating the same misguided approach, a recent newspaper front page featured a young boy with the headline, ‘How We Stop This Kid Becoming a Monster’.

This followed an earlier social marketing campaign, in which a little boy who slams a door on a little girl grows up to become a domestic abuser. The suggestion is that all boys are at equal risk of becoming violent men and, therefore, work to reduce violence against women must remain targeted at that universal level. Situating all little boys as potential perpetrators not only risks diluting much needed resources and effort, but it also invites confusion and potentially backlash from boys and young men who were never at risk of hurting their partners in the first place.

The success of the Australian HIV response was not secured by frightening suburban mums and dads who were never a risk. It was secured by resourcing affected communities, and community-led services, so they could use their knowledge and expertise to connect with those most at risk and implement effective strategies.

In other words, HIV prevention succeeded because it worked with people most at risk, not with people least at risk.

In the 1990s, the prevention messaging on HIV was almost exclusively focused on condom use and safe sex. Getting men to use condoms in significant numbers is no small feat – you’re essentially trying to change behaviour at one of the most intimate moments of a man's life, and at a point when, frankly, rational decision-making is not always front of mind. Achieving high levels of condom use required mass distribution of condoms so that they were physically available at the moment when men were going to have sex - and then normalizing condom use not only to protect yourself, but also to protect your partner. While this strategy was very successful, almost halving the number of men engaging in unprotected sex in the 1990s, from the late 90s onwards, it became less and less effective (Prestage et al., 2005). This was partly because HIV medication became more effective, but also because men basically got tired of being told to wear condoms all the time.

Over the next few years, we saw a slow but very steady increase in rates of HIV infections. The HIV prevention sector looked at the rising infections, and it made a dramatic decision to pivot. This pivot risked 20 years of messaging about condoms to the LGBT community. But the old ways weren’t working.

Instead, the messaging became:

1. Get tested and get tested often.

2. If you're negative, go on PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis). If you take this medication, you will significantly lower your chance of HIV infection.

3. If you are positive, take medication, drop your viral load and then you will be very unlikely to transmit HIV.

The implementation of this new strategy in 2016 in New South Wales had immediate results. Within one year, new HIV infections amongst men who have sex with men declined by one quarter, the state’s first substantial decrease in over a decade (Grulich et al., 2018). This trend has continued to the point where, in the epicentres of the old epidemic, HIV transmission may be eradicated in the next decade. It was a specific message, aimed directly at the community most affected, and resourced appropriately. (Results haven’t been as strong in the outer suburbs of Sydney – areas with fewer resources and lower access to testing – where infection rates are only down by about a third, which is particularly affecting CALD and Indigenous people).

To some, the Albanese government’s stated ambition to end violence against women and children in a single generation sounds absurd. But it’s worth remembering that, back in 1999, few people would have imagined that, within 25 years, HIV would be on the brink of being eliminated in Sydney. But that’s what happened. We are now having a realistic conversation about the end of HIV in Australia’s largest capital city in a single generation.

We wouldn’t be having this conversation if the sector had persisted with its original strategy. The HIV sector had an entrenched and much-rehearsed message, which was condom reinforcement. When it wasn't working, the sector put decades of hard-earned prevention messaging on the line and pivoted to a message that was, potentially, much less clear. Whereas condoms are clearly situated as a primary prevention strategy, since they prevent HIV infection before it occurs, testing and treatment are typically understood as downstream, tertiary responses that occur after exposure or infection. And yet adding these elements to the prevention response proved to be a game-changer.

On the face of it, these two crises – HIV and gendered violence – may seem too disparate to be directly comparable, at least in the Australian context (in other countries, these two epidemics closely intertwine). However, both HIV and gendered violence are conceived of as public health problems, and prevention strategies are developed in line with a public health model. We see the HIV prevention pivot as analogous to our suggestion to pivot our current primary prevention approach to gendered violence because it also involves risk, and the potential to undermine existing strategies and achievements.

Condom-use, for example, is a broader good – not just for preventing HIV, but also other STDs (as well as unwanted pregnancy in heterosexual couples). To pivot away from that message risked undermining the benefits of protected sex and wasting years of investment in time and money; it also risked confusing the public about the best method for preventing HIV. Gender equality is also a broader good, and a pivot away from that focus in the violence prevention space may feel like it is similarly risking the gains already made, the community support for that goal, and the infrastructure in place to keep pursuing that strategy.

As few would argue against the importance of wearing condoms, few would argue against the importance of achieving greater gender equality and changing violence-supporting attitudes across the community. But just because these are worthy aims, doesn’t mean they are the most effective when it comes to preventing gendered violence. And if we’re not seeing results, we need to have the courage to talk openly about taking a different approach.

We are arguing for a much more targeted approach, one that doesn’t focus so heavily on the notion that ending gendered violence is the responsibility of everyone but recognises that particular population groups need greater focus and resourcing than others, and also that some sections of the community, our systems and industries have greater power and responsibility to affect change.

****

We are also making this argument now because we cannot risk taking the same dead-end approach we have seen in other areas – most notably, on global warming. The dominant message on global warming for decades was that everyone was responsible; it emphasised individual actions, like using low-energy lightbulbs and recycling, but failed to target the large emitters of greenhouse gases.

We all do have a role to play, both in reducing global warming and in ending gendered violence, but those roles and responsibilities are not equal. 14-year-old Harry does not have the same role or responsibility for ending gendered violence as say, the owners of Tik Tok or PornHub. Harry can help out the environment by not using single-use plastic, but his role is not equal to the multi-billion dollar industries responsible for the vast majority of emissions.

Prevention strategies and programs to reduce gendered violence have often relied, implicitly or explicitly, on a kind of collective guilt in which all men as a group are deemed responsible for men’s violence against women by dint of being male. The very notion of collective guilt or responsibility is a contested one in moral philosophy and raises complex questions, including whether “men” can be meaningfully understood as a collective who can be held accountable for each other’s actions. However, those questions aside, telling men and boys that if they make sexist jokes, or fail to challenge the attitudes of their mates, they are personally responsible for the physical and sexual violence or homicides committed by other males has not proven a compelling or successful argument.

At least in theory, guilt is an aversive emotion that should increase the inclination to make reparations for the harms inflicted by an individual or a group. However, social psychological research suggests that guilt can motivate support for symbolic gestures such as apologies, but it does not necessarily compel concrete or effective action (Faulkner, 2014). A prevention program coordinator working in an Australian university described this dilemma in his efforts to engage male students:

I spent probably about eight months asking people to come to groups they didn't come to … I'd be publishing information about the number of women who were impacted by it [violence] and [saying] “this is your mother and your sisters and you've got a responsibility”. But none of those things were actually like sort of [working] … I was getting nothing (Carmody et al., 2014).

However, even if we could engage boys and men en masse, and even if we were able to change their attitudes to gender and equality, it’s not clear that this would lead to a reduction in gendered violence. We need to consider evidence that suggests that even when gendered norms, attitudes and levels of equality are drastically improved, gendered violence remains stubbornly high.

This is known as the ‘Nordic paradox’, because in the Nordic countries that rate highest for gender equality - where women enjoy better rights, greater legal protection and more equal access to power - rates of gendered violence are, according to population surveys and other data, even higher than the EU average (Gracia & Merlo, 2016). These findings can no longer be ignored. We must grapple with the very real possibility that we could spend tens of millions more dollars pushing for greater gender equality and norms-change as our primary violence prevention strategy without actually reducing violence against women.

Briefly, here is some of the key evidence that supports this concern.

On the WEF scorecard for the world’s most gender equal countries, Scandinavian countries dominate the top five: in order, that is Iceland, Norway, Finland, New Zealand and Sweden (Australia was ranked 26th globally in 2023 on the WEF Global Gender Gap Report – a vast improvement from 43rd the year before).

So let’s look at Iceland, for starters. It’s been ranked number one for 14 years in a row. It has a female prime minister. Half of Iceland’s MPs are female, and a high number hold managerial and executive positions. Parental leave conditions for mothers and fathers enable nearly 90 percent of working-age women to have jobs (compared to about 60 per cent of Australian women).

But Iceland continues to have high levels of violence against women, particularly sexual violence. One in four women say they've been sexually assaulted; 50% of murders in Iceland are committed by male partners, compared to the global average of 38% (Jóelsdóttir & Wyeth, 2020). Only 12% of women in Iceland report sexual violence; and most cases fail to make it to trial. In fact, the persistent level of gendered violence is so bad in Iceland that tens of thousands of Icelandic women just took part in the first nationwide women’s strike since 1975, stating two main reasons: the prevalence of gendered violence, and the remaining gender pay gap (which the OECD puts at 10 per cent, just below Australia at 12 per cent). “The struggle for equality has not resulted in less gender-based violence,” said Drífa Snædal, a frontline worker and strike organiser, to the New York Times.

But it's not just Iceland. If it were, we could say well, maybe it’s just unique to that country - it's dark for three months of the year, and maybe they just haven’t addressed problematic gender norms like we’re doing here.

But this trend repeats across countries that score high for gender equality. It’s been shown in several surveys; to cite just a couple, we have one from 2012 that shows that Finland, which generally ranks third worldwide for gender equality, also ranked third in the EU for levels of intimate partner violence. Another national survey by the National Council for Crime Prevention in Sweden from 2014 showed that more than one in four women have at some point in their lives been victimized in a close relationship. Again in 2014, an influential survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), which interviewed 42,000 women across the European Union, found the lifetime prevalence of physical and sexual violence from current and former intimate partners was for Denmark, 32 per cent, Finland, 30% and Sweden, 28% - well above the EU average of 22% (and above the Australian average of 25 per cent).

The FRA used the same methodology as the Personal Safety Survey here in Australia, which asks questions about specific acts of physical and sexual violence (and is considered our best source of data on the subject).

As you can imagine, many of the Nordic countries rejected these survey results. They said it could likely be explained by the fact that their citizens have a better understanding of what constitutes gendered violence, and when they are experiencing it. The surveyors certainly conceded that in some countries, it is less culturally acceptable to talk with other people about violence and may have inhibited women in some countries from talking honestly. Regardless, in comparison to Australian data, which shows 1 in 4 women since the age of 16 have experienced gendered violence, those numbers are much higher than one would have expected.

Across the Tasman in New Zealand, rates of gendered violence also remain stubbornly high, and recent national statistics show that when it comes to coercive control in particular, those rates are rising. Comparing data from 2003 and 2019, researchers at the University of Auckland found that women reported increased lifetime experience of controlling behaviours and double the rates of economic abuse from a male partner. The lifetime rate of physical intimate partner violence (IPV) has not changed (though prevalence had halved in the 12 months previous to 2019, compared to 2003) and there has been a small reduction in lifetime sexual IPV. New Zealand has ranked in the top 10 for gender equality since the index was launched in 2006.

In Australia, another study from ANU gives further context to what we’re seeing in the Nordic countries. It found that women who earn more than their male partners are 35% more likely to be subjected to physical violence, and 20% more likely to be subjected to emotional abuse (Zhang & Breunig, 2021). This again suggests that men losing status (or perceiving themselves to lose status) is a risk factor for violence and the use of coercive control. Professor Robert Sapolsky, one of the world’s leading experts on biology and neurology, speaks to this dynamic when he explains (in his book, Behave) that when testosterone rises after a challenge, it doesn’t prompt aggression. ‘Instead,’ writes Sapolsky, ‘it prompts whatever behaviours are needed to maintain status.’ In other words, testosterone is not an aggression hormone – it is a status-seeking hormone (Sapolsky, 2017).

We are not arguing against the pursuit of gender equality – obviously, we want to see vast improvements in this area. What we are saying is that improved levels of gender equality may not actually lead to an actual reduction of gendered violence, especially in the short- to medium-term. In fact, we should be prepared that as gender equality increases, we may see an increase in gendered violence. Frontline workers in Nordic countries explain this, partly, as a result of backlash and male resentment. They talk about getting too comfortable simply pursuing and celebrating gender equality and norms change, but lacking systems reform and consistent accountability measures for perpetrators.

In Australia, policy frameworks acknowledge the possibility of male backlash against anti-violence strategies, but what’s our strategy for managing it? How will education in schools override the social education young boys and men are getting from social media algorithms, particularly through TikTok and YouTube? How will it offset the effect of watching violent, misogynistic porn from an early age, often occurring before children reach puberty? Of course, consistent education on these issues is vital, but we seem to be, over and again, putting all our eggs in the basket of education and awareness raising.

The grounding of our current primary prevention approach is within a safe, liberal, progressive framework, which proposes that our social and cultural context communicates messages to boys and men, a bit like a radio transmitter. According to this framework, boys and men are on the wrong frequency, tuning into Andrew Tate, sexist jokes and male entitlement, and our job is to shift the dial to the right station. They've got the wrong message, which is why some of them use or excuse gendered violence; they need the right one. However, when we speak to men’s behaviour change program facilitators, and with men who themselves use coercive control and violence, one of the things we hear consistently is that, even if those men had been subjected to the prevention interventions that we have in place now, it wouldn’t have interrupted their pathway. Norms, values, awareness-raising, education programs – they’re all highly cognitive. They involve thinking and learning – which requires that those receiving the lesson are not feeling threatened or distressed – and they fit very well within a white middle-class model of behaviour change.

Pathways to committing gendered violence are not just attitudinal – they are biographical. Those pathways are formed through the lives that men have led, and the ways that violence and coercive control becomes a meaningful and available choice to some men and boys but not others. This pathway to abuse is often developmental, beginning in childhood, grounded in life events that are averse, abusive or violent. These life events become encoded in men’s minds, but also in men’s bodies (known in psychology as ‘affect’), as a propensity towards aggression, oppression and violence that is then very difficult for us to unpick as they start to move through life stages – the accumulation of experiences, decisions and choices over time. Abuse can become steeped in the felt experience of emotional suppression and denial, dysregulation, trauma, substance abuse, depression, suicidality; all of which we know are factors that are often clustering in the lives of boys and men who choose to use violence. That’s not to say that men who use violence and coercive control all come from abusive backgrounds, and certainly this is not a class issue. As the Australian feminist author Jocelyn Scutt (1983) famously put it over forty years ago, family violence occurs “even in the best of homes”. This is especially true for coercive control, particularly cases where physical violence is used sparingly, or not at all. We know also that sexual violence is perpetrated by a wide variety of boys and men.

However, in our current prevention model, there does seem to be a default middle-class subject sitting at the centre of our interventions; a tabula rasa upon which we can imprint the right beliefs and attitudes. The moment that we start to acknowledge some complexity in the life of a boy or a man – perhaps he was removed from his parents as a child by welfare services, maybe he grew up in a house with domestic violence, or he has a drug or gambling problem, or he was sexually abused when he was young – that individual ceases to be a proper target for primary prevention. We are told that he now comes under the umbrella of what is called “secondary prevention” or “early intervention”, because he has “risk factors”.

In fact, most people's lives are complicated, and that’s particularly true of violent and oppressive men. The concept of a “risk factor” is an abstraction that we’ve created to help make sense out of the messiness of life, but for the man who’s living within that messiness, it is his “normal”, and probably also the “normal” of his family and community. A primary prevention approach unable to engage with the messiness of different kinds of “normal” may preserve its ideological hygiene but risks sacrificing impact and efficacy.

It's not easy or pleasant to enter into the perpetrator's perspective and to try to understand him in his own terms. But if we refuse to do that, then we fail to understand how the drive for violence and control gets its tendrils deep into the minds and bodies of so many men and how it stays there, like a parasite. We say that violence is a choice, and it is - but not all choices are the same. Gendered violence is not a choice in the way that we make a choice when we go to the supermarket and pick a brand of toothpaste off the shelf. And for a non-violent man, the choice not to use violence and/or oppressive tactics is not much of a choice at all. Violence doesn't make any sense in the lives of most men, and though power is contested in many ways in relationships and families, most men do not feel the need to degrade, control and entrap their partners and kids. Most men are not moving through their day making a continual choice not to use violence and/or coercive control. And for the men who are choosing to use violence and abuse, it’s is an option because it fits within their experience of the world that they've grown up in, no matter how paranoid or delusional or narcissistic the world that they experience may be. When those men and boys (from all classes and cultures) are violent, they commonly present themselves as victims, and they do so incredibly passionately, because that is very much how they wake up and experience themselves and their world. If we fail to engage with and address the depth of the logic of violence and control within such men and boys, we have little hope of helping them access alternative pathways.

Furthermore, if our entire focus is on education, and changing norms and attitudes - all these cognitive strategies to change men and boys - if that’s the strategy we lean most heavily into, it does start to tip into re-education. Some forms of education and some awareness campaigns can also drift into framing maleness as bad, albeit sometimes unintentionally. We must be cautious of any drift into intolerance to diversity, and the autonomy of men and boys to think and feel more or less what they want to think and feel - the freedom we all have - as long as they don't engage in controlling and/or violent behaviours towards women and children. Educating and engaging boys and men is incredibly important, but it must be done in ways that truly connect with them, as programs like She is Not Your Rehab (Brown & Brown, 2021) exemplify, and we cannot afford to hinge our prevention efforts on our ability to change their minds.

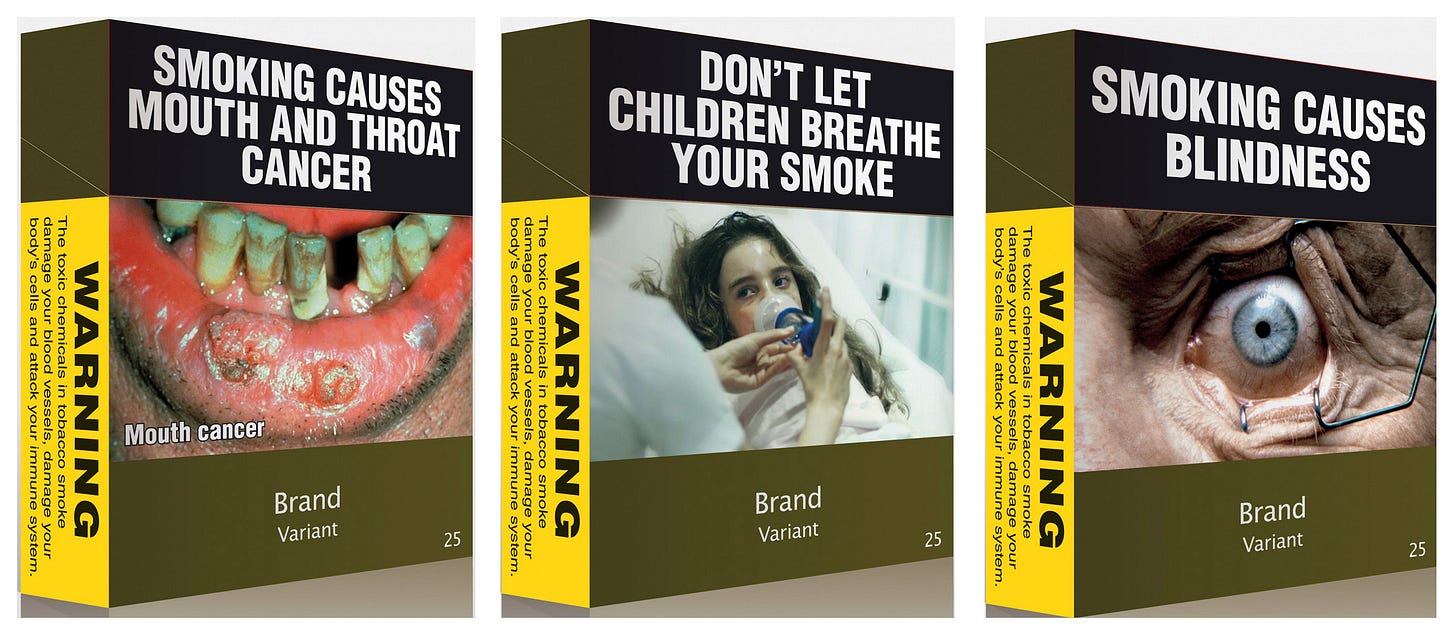

A useful parallel comes from another Australian public health success, namely smoking reduction. We don't need people to become anti-smoking activists; we just need them to stop smoking, right? Yes, we told people that it's bad to smoke, it's wrong to smoke. It hurts you and it hurts other people. But the success of our anti-smoking campaign wasn't just cognitive. We made smoking an increasingly difficult choice to make. We made it an expensive choice by raising taxes. We made it a choice that you can't make when you're inside a building, or even within four metres of one. We made it hard to just buy cigarettes. We took on the legal might of big tobacco companies to replace their packaging with drab olive-green wrappers featuring gory photos of harm and death.

We made the choice to smoke - it's still a choice - unappealing, and often unavailable. The question is, how do we replicate that success when it comes to ending men’s violence against women and children?

****

So what is missing? That’s a big question, with a range of possible answers. No country can claim to have solved the problem of violence against women. But we also know that gendered violence is not inevitable.

Rates of domestic and sexual violence go up and down between countries and locations, and change over time, which proves that there is no single "fixed” rate of violence. In Australia, certain types of violence have been trending downwards for decades. Homicide has more than halved in Australia since 1990, linked to increased gun control (Ramchand & Saunders, 2021) and reduced alcohol intake (Ramstedt, 2011). In the last 15 years, physical assault has declined by a third, which Don Weatherburn (former director of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research) attributes to reduced alcohol intake amongst young people, against a backdrop of rising alcohol prices (Weatherburn & Rahman, 2021). At the same time, sexual assault has remained high, while rates of reporting of sexual assault to police have increased dramatically.

While Australia has seen significant reductions in some kinds of crime, particularly public and street violence (typically between men), private and intimate kinds of violence – such as domestic and sexual violence – have proven more resistant to change. However, where reductions in femicide and domestic violence have occurred, contributors to prevention have been practical and material rather than cultural: particularly, gun control and alcohol prices. If we are committed to keeping women and children safe, then any and all solutions should be on the table. Solutions must be integrated into a systematic prevention response that takes advantage of every opportunity to prevent violence before it occurs. The list of targets that we present here is by no means exhaustive, but they strike us as some missing pieces to the puzzle of prevention.

1. Accountability and consequences

2. Prevention of, and recovery from, intergenerational trauma and child abuse

3. Address the socioeconomic impacts and gradients of domestic and sexual violence and coercive control

4. Address the commercial determinants of domestic and sexual violence and coercive control

Accountability and consequences.

This means both accountability for the success of prevention work, accountability for systems, and accountability and consequences for perpetrators as a means of prevention.

Our current primary prevention model outsources its results to future generations, and thus gives politicians the cover to adopt platitudes and evade accountability. If the sector is telling our politicians to focus on gender equality, re-educating young boys and men and changing community attitudes, but does not say, “you need to confront some vested interests and change policy settings that increase rates of violence and we’re going to make a lot of noise about it until you do”, then the government simply will not burn the necessary political capital.

The federal government, for example, recently rejected the e-Safety Commissioner’s roadmap to establish age verification for online porn. The sexual violence sector was barely consulted about this, despite the strong evidence that children’s exposure to pornography is resulting in more severely harmful sexual behaviour, as well as other sexual behaviours amongst boys and young men (like non-fatal strangulation and spitting during sex) that girls and young women often do not want or enjoy; certainly, most do not often appreciate the danger inherent to strangulation. The status quo grants the mainstream porn industry free access to men and boys, negatively influencing sexual behaviour. We need to be campaigning for the hard political actions that will actually have a material impact on community norms and change how young boys and men think about sex and gender in ways that reduce sexual violence. We need to tell the government, here are the difficult fights we need you to take on.

We cannot rely on the National Community Attitudes Survey to measure the progress of our National Plan. It should be an utmost priority of government to develop a measurement tool that captures data relevant to the objectives of the National Plan, as well as measure the prevalence of coercive control. Only when we have baseline data will we be able to account for whether our efforts are having the desired effect.

Critically, we also need to see offender accountability as core to prevention. To quote sexual violence expert Angela Lynch, ‘accountability is prevention’. We're not just talking about stopping someone from becoming violent at all. We're talking about stopping them from being violent to their current partner, their next partner and their next partner. Prevention strategies are now focused on stopping men from becoming perpetrators; we would like to direct more focus towards stopping them from creating one more victim. Strategic policing and disruption that targets domestic violence perpetrators with a known history and high risk of reoffending is prevention if it saves one life or stops one more woman being subject to his violence. There is evidence that a small group of sexual violence perpetrators are responsible for multiple rapes (Lisak & Miller, 2002): identifying and incapacitating these men as soon as possible would limit the scope of their damage.

A recent survey asked more than 1100 victim survivors what they thought would help stop the violence. Four key responses emerged:

1. A fear of the consequences

2. Holding them to account

3. Removing myself

4. Nothing was helpful

These victim survivors defined accountability and consequences as a) through legal systems, and b) through networks of family, friends and professional networks. Most women surveyed were, however, “deeply pessimistic” about the potential for their partner/ex-partner to stop being abusive.

As these victim survivors expressed, accountability can come in many forms – not just the criminal justice and civil protection system, although making those interventions effective and protective is critically important. We are seeing some targeted focused deterrence work in various states: NSW Police, for example, have been using a form of focused deterrence with Operation AMAROK, comprising multiple waves of ‘blitzes’ lasting four to five days, in which hundreds of high-risk and known domestic violence offenders are located and charged with Apprehended Domestic Violence Order breaches and any outstanding warrants. We need to be evaluating interventions like these, their impact on recidivism and the safety of victim survivors. We also need a strategy for engaging these offenders over the longer term, and where possible and appropriate, connecting them to therapeutic programs.

For some victim survivors and offenders, other forms of accountability and consequences will be more effective and meaningful. When the major banks detect persistent financially abusive behaviour, for example, they are suspending, cancelling or denying the offender access to their account (amongst other consequences for such behaviour) (Hendy, 2023), thanks in large part to the pioneering work of former bank executive and systems reform expert, Catherine Fitzpatrick.

There is a great opportunity here to introduce accountability and consequences across the many systems currently weaponised by perpetrators, from child support to Centrelink and the family courts. Systems abusers should be identified by these systems and face consequences, instead of being allowed to carry on with impunity, and benefit from their abuse.

Alternative and complementary justice responses also warrant further investigation and investment. For example, phase three of the restorative justice scheme in the ACT, which was expanded to include domestic, family, and sexual violence offenders, was recently evaluated by the Australian Institute of Criminology and delivered promising results in terms of healing, improved safety, and offender accountability (Lawler, Boxall & Dowling, 2023). We are seeing justice reinvestment programs trialled in different locations around the country; when JR was introduced in Bourke, the results in the first few years were stunning, including around a 30 per cent reduction in domestic violence-related assaults, an increase in rates of high school graduation, and historically low rates of child removal. There are community-run intervention models like this that we should be exploring as strategies to stop violence that already exists, to prevent it from being repeated.

Key to ensuring accountability for perpetrators is making systems accountable, too. The sector and survivor advocates have been campaigning for years for greater accountability and oversight over police, child protection and the family law system. Perpetrator accountability will only be possible when the systems that respond to them are accountable, too.

We need a stronger focus on both the prevention of, and recovery from, intergenerational trauma and child abuse.

Child abuse and neglect – including growing up with coercive control, being physically or sexually abused, being shamed and/or neglected by parents – are accelerants to adult victimisation and perpetration. Traumatised and abused girls who are not supported to recover and heal are more likely to be targeted by violent and controlling perpetrators throughout their lives. Often, this cycle is only interrupted when they realise that their adult experiences of violence are connected to the stark lessons imparted to them by childhood trauma, which often has the effect of normalising grooming and maltreatment and blinding them to ‘red flags’ and boundary violations. At the same time, traumatized boys are disproportionately at risk of becoming perpetrators of gender-based violence, and other forms of criminal behaviour.

The gendered differences in conduct between traumatised boys and girls are often explained as cultural. A frequent explanation is that boys and girls are impacted by trauma in identical ways, but social and cultural norms lead abused boys to act out. However, decades of evidence across multiple disciplines show that boys are particularly fragile when exposed to trauma and disadvantage. As neuropsychologist Allan Schore (2019, p. 84) explains:

The idea that the growth and maturation of males is affected more adversely by early environmental stress than it is for females has a long history in the biological, medical and anthropological literature.

Summarising decades of developmental research, Schore (2019, p 89) shows that boys’ brains develop at a slower pace than girls and, as a result, “boys are more vulnerable over a longer period of time to stressors in the social environment” compared to girls. On average, female children can better regulate their emotions, signal for help to caregivers and articulate their needs at a younger age compared to boys. In contrast, when exposed to stress or difficulty, male children are more likely to experienced prolonged overwhelming emotion that they cannot regulate, resulting in profound states of anger and overwhelm that lay down the early architecture for aggression, fear and control. Traumatised boys are less prepared for school even compared to their sisters who have been subject to the same maltreatment, and their behaviour is more likely to become unruly and aggressive (Reeves, 2022)6. Steeped in a culture of male violence and aggression, the pathway to violence and coercive control is familiar.

This is not a simple argument from biological essentialism. Schore (2019) describes in detail the relationship between the cultural environment, parenting behaviours, attachment patterns, and the developing neurophysiology of male and female infants. Clinicians who work in the complex trauma field such as Elizabeth Howell (2002) have long argued that gender stereotypes and rigid gender norms become fixed through traumatic processes: aggression and entitlement in men, shame and self-blame in women. It is simply undeniable that there is an over-representation of child abuse survivors amongst men who use violence against their partners.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Aboriginal advocates, we’re now prepared to talk about the victim-to-perpetrator pathway for Indigenous men who offend. However, in the next breath, we talk about non-Indigenous men who perpetrate violence and coercive control as simply wrongly educated products of bad gender norms, for whom family and community trauma histories are largely irrelevant. We need a much greater working relationship with the child abuse prevention sector, and serious funding and resources to help child victim-survivors and their mothers recover, so they can heal together as a family. The work that we're doing around preventing child abuse and maltreatment, preventing violence against women, and healing from trauma and abuse, all needs to be linked. Rosie Batty made one of the most important interventions in this space a couple of years ago, when she and the National Recovery Alliance said, ‘Recovery is Prevention’. They looped the circle, where instead of putting prevention at the very beginning and recovery right at the end, they made a previously linear concept circular. There is no beginning and end to prevention – prevention work must be done across the life cycle - and recovery particularly feeds directly into prevention work.

We need to address the socioeconomic impacts and gradients of domestic and sexual violence and coercive control.

The unofficial reserve army of prevention agents in this country are single mothers who are survivors of domestic violence. They are doing largely unsupported work with their own children - who may also be perpetrating violence against their other children or even against them - so they don’t grow into adults who either use violence or are subjected to violence or coercive control. For survivor families, we need to be looking at practical prevention measures. While all social classes experience violence, national and international research suggests that women who live in poverty experience more violence, more severe violence, and have less opportunity to ameliorate its impacts.

The most impactful research and campaigning work we've seen in the last couple of years came from Professor Anne Summers, who was in 2021 living in New York City when she thought, Why don't I have a look into the Personal Safety Survey to find out what do we know about the connection between single mothers and domestic violence? Summers unearthed data showing that not only were 60% of single mothers survivors of domestic violence; 50 per cent of them were now living in poverty with their children (Summers, 2022). What Summers showed conclusively through existing national data was that poverty does not cause domestic violence; domestic violence causes poverty. Together with Terese Edwards, CEO of the National Council of Single Mothers and their Children (who had been campaigning tirelessly since the single parenting payment was cancelled) Sam Mostyn AO, and several other advocates and lived experience campaigners, Dr Summers made the federal government realise and care about the fact that this policy change had entrenched poverty among thousands of single parents – the majority of them domestic violence survivors. This data, dormant within the 2016 Personal Safety Survey for years, was only uncovered because Anne Summers asked the right questions. Thanks to this research, then an intensive lobbying campaign, the single parenting payment was restored in this year's budget for single parents with children aged up to 14. And while we celebrate that achievement, it also feels too piecemeal. Where is the broader prevention focus on changing bad laws, and fighting for policy changes that will have a material impact on the lives of families and individuals most at risk?

We need to address the commercial determinants of domestic and sexual violence and coercive control.

When it comes to the prevention of violence against women, what do we have to say about children watching X-rated pornography? What do we have to say about alcohol regulation? What do we have to say about problem gambling? Other public health models will seek to regulate or prevent the sale of goods that contribute to or cause disease. Violence prevention frameworks around gender-based violence in Australia have been reluctant to tackle wealthy industries that are profiting from violence against women, such as pornography and the technology sector, and the multi-billion dollar alcohol and gambling industries. We know that young people feel that pornography is normalising sexual practices that girls and women describe as painful or unpleasant (Marston & Lewis, 2014). We know that the majority of alcohol sales are going to people who are drinking at harmful levels (Foundation for Alcohol Research Education, 2016). We know that the number of liquor shops in your local suburb is causally related to the prevalence of domestic violence independent of any other demographic factor, including class (Livingston, 2010). We know that problem gambling is an accelerant to family violence (and a form of financial abuse) (Dowling et al., 2016). Even if we don’t consider alcohol or substance misuse to be the cause of family violence/coercive control, and simply see it as an exacerbating factor – isn’t it incumbent on us to tackle the factors that exacerbate violence, and lead to more severe physical injuries?

The regulation of industries who are engaged in harmful commercial behaviours is standard public health practice and needs to be factored into our strategies for reducing gendered violence. In our current primary prevention approaches, the private sector is predominantly engaged in terms of education and training to create safe and respectful workplaces, and so on. That's obviously important, but there is no mention of business models that are actually causing and/or exacerbating gendered violence. The notion that 13- and 14-year-old boys should change their ways in order to reduce the level of violence against women, but those sitting in corporate suites with huge sums flowing into their personal bank account have no responsibility, seems deeply inequitable. We think that disparity is very problematic and needs to be corrected.

****

We are living with an epidemic of gendered violence. We cannot afford to be constrained by artificial conceptual distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary responses.

We need a coordinated model of prevention that targets multiple levels and forms of risk simultaneously; that is calibrated to the scale of need; that is adaptive to signals and feedback from the frontline; and that responds to new evidence as it emerges.

Primary prevention is not limited to universal strategies. It is not limited to whole-of-population interventions. Primary prevention is, quite simply, anything that reduces the level of violence against women and children.

Somewhat ironically, this is the model primary prevention model first articulated in the World Report on Violence and Health (from the World Health Organisation) over twenty years ago, the foundational document that inspired Australia’s pioneering efforts to prevent gender-based violence and abuse (Krug et al. 2002). The World Report (2002) stated explicitly that primary prevention “is most effective when carried out early, and among people and groups known to be at higher risk than the general population” (p 248). It also recognised that opportunities to prevent gender-based violence are present across the lifespan, from the pre-natal environment to elderly care; that prevention will look different in different community contexts; and intervention points can be traced from the highest levels of government decision making down to how we respond to abused children and women, and our willingness to support them to heal and recover.

Just as a policy or program is part of the prevention arsenal if it reduces the rate of HIV infection – from safe sex messaging to pre-exposure prophylaxis, testing, and treatment – a policy or program is ‘prevention’ if it prevents one more man from harming one more woman or child. And if we find that certain interventions have a greater impact than others, then we should give them greater focus and investment.

Importantly, we need to meet men and boys where they are at - particularly those who disagree with us, who are hostile to the memes and slogans shared by prevention agencies, who have normalised the violence and abuse they themselves have often been subject to, and those who have a deep-seated need to control the people they are closest to. We could even do something radical and ask them what they think would work!

We anticipate a response from some policy makers to this paper may be that they are already undertaking many of the activities that we’ve listed above. It’s true that there is innovative and exciting work being done across the response system to gendered violence in Australia. However, this work is not being acknowledged for its preventative effect, nor is it being integrated into, resourced and coordinated within prevention frameworks.

As state and federal governments seek to design and implement primary prevention strategies, they must not limit these strategies to education and attitudinal change. It is insufficient to simply point to the preventative potential of the other strategic ‘pillars’ – early intervention, response and recovery –as the Queensland government has done in its recently released primary prevention strategy. Where is the investment in these other forms of prevention? Where is the focus? We also believe it is time for well-funded and generously staffed prevention agencies to expand their approach to prevention, and work more closely with the frontline to reduce the prevalence of abuse in the short- to medium term.

There is no panacea to gendered violence. There is no one solution. We will not go close to achieving the government’s ambitious goal to end gendered violence within a generation unless we pursue a prevention agenda that aims to prevent gendered violence and coercive control within the short- to medium-term.

We need a flourishing and interconnected prevention system, embedded in and connected to frontline services, with appropriate resourcing and incentives to focus where they have the most preventative effect. And ultimately, as prevention advocates, we need to hold ourselves accountable to the goals that we set for ourselves and the promises we make to the community.

REFERENCES

Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, 2022. https://anrowsdev.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ALSWH-SV_in_childhood_risk.pdf

Bloom, M., & Gulotta, T. (2014). Definitions of primary prevention. In T. Gulotta & M. Bloom (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion (pp. 3-12). Springer.

Brown, M., & Brown, S. (2021). She Is Not Your Rehab: One Man’s Journey to Healing and the Global Anti-Violence Movement He Inspired. Penguin.

Carmody, M., Salter, M., & Presterudstuen, G. (2014). Less to lose and more to gain? Men and boys violence prevention research project final report. Western Sydney University. https://researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:26711

Coumarelos, C., Weeks, N., Bernstein, S., Roberts, N., Honey, N., Minter, K., & Carlisle, E. (2023). Attitudes matter: The 2021 National Community Attitudes towards Violence against Women Survey (NCAS), Findings for Australia. (Research report 02/2023). ANROWS.

Dowling, N., Suomi, A., Jackson, A., Lavis, T., Patford, J., Cockman, S., Thomas, S., Bellringer, M., Koziol-Mclain, J., & Battersby, M. (2016). Problem gambling and intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(1), 43-61.

Foundation for Alcohol Research Education. (2016). Risky Business: The Alcohol Industry's Dependence on Australia's Heaviest Drinkers. FARE. https://fare.org.au/risky-business-the-alcohol-industrys-dependence-on-australias-heaviest-drinkers/#:~:text=Risky%20business%2C%20a%20new%20report,significant%20segments%20of%20the%20population.

Gracia, E., & Merlo, J. (2016). Intimate partner violence against women and the Nordic paradox. Social Science & Medicine, 157, 27–30.

Grulich, A. E., Guy, R., Amin, J., Jin, F., Selvey, C., Holden, J., Schmidt, H.-M. A., Zablotska, I., Price, K., & Whittaker, B. (2018). Population-level effectiveness of rapid, targeted, high-coverage roll-out of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: the EPIC-NSW prospective cohort study. Lancet HIV, 5(11), e629-e637.

Hegarty, K., McKenzie, M., McLindon, E., Addison, M., Valpied, J., Hameed, M., Kyei-Onanjiri, M., Baloch, S., Diemer, K., & Tarzia, L. (2022). “I just felt like I was running around in a circle”: Listening to the voices of victims and perpetrators to transform responses to intimate partner violence (Research report, 22/2022). ANROWS.

Heise, L. (1994). Gender-based abuse: the global epidemic. Cadernos De Saúde Pública, 10(suppl 1), S135–S145.

Hendy, N. (2023, October 2). Financial abusers to be cut off from accounts as banks crack down. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/money/banking/financial-abusers-to-be-cut-off-from-accounts-as-banks-crack-down-20231003-p5e9a3.html.

Howell, E. F. (2002). “Good girls,” sexy “bad girls,” and warriors: The role of trauma and dissociation in the creation and reproduction of gender. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 3(4), 5-32.

Jóelsdóttir, S. S., & Wyeth, G. (2020, July 15). The misogynist violence of Iceland’s feminist paradise. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/07/15/the-misogynist-violence-of-icelands-feminist-paradise/

Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., & Lozano, R. (Eds.). (2002). World Report on Violence and Health. World Health Organisation.

Lawler, Boxall & Dowling (2023). Restorative justice conferencing for domestic and family violence and sexual violence: Evaluation of Phase Three of the ACT Restorative Justice Scheme, The Australian Institute of Criminology. https://www.justice.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2315832/FINAL-REPORT_18Oct_Public-version.pdf

Lisak, D., & Miller, P. M. (2002). Repeat rape and multiple offending among undetected rapists. Violence and Victims, 17(1), 73-84.

Livingston, M. (2010). The ecology of domestic violence: the role of alcohol outlet density. Geospatial Health, 5(1), 139-149.

New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse. (n.d.), New research finds changes in rates of intimate partner violence in NZ. https://nzfvc.org.nz/news/new-research-finds-changes-rates-intimate-partner-violence-nz)

NSW Domestic Violence Death Review Team (2020), Report 2017-2019. https://coroners.nsw.gov.au/documents/reports/2017-2019_DVDRT_Report.pdf

Prestage, G., Mao, L., Fogarty, A., Van de Ven, P., Kippax, S., Crawford, J., Rawstorne, P., Kaldor, J., Jin, F., & Grulich, A. (2005). How has the sexual behaviour of gay men changed since the onset of AIDS: 1986–2003. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 29(6), 530-535.

Ramchand, R., & Saunders, J. (2021). The Effects of the 1996 National Firearms Agreement in Australia on Suicide, Homicide, and Mass Shootings. Contemporary Issues in Gun Policy: Essays from the RAND Gun Policy in America Project, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-A243-2, 43-65.

Ramsay, J. (2004). The Making of Domestic Violence Policy by the Australian Commonwealth Government and the Government of the State of New South Wales between 1970 and 1985: An Analytical Narrative of Feminist Policy Activism

Ramstedt, M. (2011). Population drinking and homicide in Australia: a time series analysis of the period 1950–2003. Drug and Alcohol Review, 30(5), 466-472.

Reeves, R. (2022). Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, why it Matters, and what to Do about it. Brookings Institution Press.

Sapolsky, Robert M. (2017) Behave: The Biology of Humans at our Best and Worst, New York: Penguin.

Schore, A. N. (2019). The Development of the Unconscious Mind (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Scutt, J. A. (1983). Even in the Best of Homes: Violence in the Family. Ringwood, Vic.: Penguin.

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. Oxford University Press.

Stylianou, M. (2010). The return of the Grim Reaper: how memorability created mythology. History Australia, 7(1), 10.11-10.18.

Summers A (2022) The Choice: Violence of Poverty. University of Technology Sydney. https://doi.org/10.26195/3s1r-4977

Thomson, A. (2023, July 24). How close is Sydney to ending HIV? It depends on where you live. Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/how-close-is-sydney-to-ending-hiv-it-depends-on-where-you-live-20230720-p5dpz0.html#:~:text=Sydney%20close%20to%20eliminating%20HIV%20in%20inner%20city%2C%20but%20not%20outer%20suburbs

Weatherburn, D., & Rahman, S. (2021). The vanishing criminal: Causes of decline in Australia’s crime rate. Melbourne Univ. Publishing.

Zhang, Y., & Breunig, R. (2021). Gender norms and domestic abuse: Evidence from Australia. In Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Crawford School of Public Policy, & Australian National University, TTPI - Working Paper 5/2021 [Report]. Tax and Transfer Policy Institute. https://taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publication/taxstudies_crawford_anu_edu_au/2021-04/complete_breunig_zhang_wp_mar_2021.pdf

This is an excellent article. I have worked in both gender-based violence response and prevention for many years and the lack of progress is very depressing. I fully support reviewing the current approach. I oversaw a project that investigated the link between gambling and family violence a number of years ago and despite the findings we simply couldn't get any government buy into the issue (even though it was funded by a government funded statutory authority). We definitely need to start thinking about how to tackle the issues that underpin frequency and severity of violence against women and children.

Excellent piece. Very encouraging to finally see some acknowledgement of the causal connection between trauma experienced in childhood, especially by boys, and their later adolescent and adult behaviour. Evidence of this has been available internationally for several decades but has not sufficiently informed Australian discussion of DV. Ambient socio-economic determinants as stressors need to be taken more seriously - they were very apparent during the lockdowns but the dots were not joined. Sexual aggression can also be driven by trauma and socio-economic disadvantage, and boys are not all inevitably seduced by porn simply because it's available. More use of half a century of research on human sexuality and its unconscious drivers would be desirable. Some coercive control is unconscious survival and compensatory strategies learned during childhood abuse and trauma and taken unconsciously into adulthood as normalised, but because the impact of trauma is not sufficiently acknowledged, and because the dominant narrative around DV assumes misogyny - which is the opposite of what is often really occurring - we still don't understand coercive controlling behaviour adequately. Childhood abuse and trauma caused not only by DV but by ANY form of abuse and disadvantage (including poverty, juvenile detention, bullying, sexual abuse etc.) can result in multiple mental health issues that are still being ignored in their contribution to alleged DV, as evidenced in responses to multiple high-profile cases. Good support for all victims at all ages and stages requires a universally and immediately accessible public mental health system, which Australia does not have, and until we DO have it, most victim survivors will be failed, and hence problems perpetuated. Resilience and recovery also require a far more socially just and inclusive and supportive society than Australia is today, which means that no matter how resilient survivors may be, they can still be failed at any later stage of their lives and revert back to previous stags of mental and behavioural distress. Suicide can be a direct consequence of DV, but suicide prevention in Australia is also still in the dark ages.